What to know about food insecurity: From minimal and stressed to crisis and famine

Amid the many headlines and reports about food crises, understanding hunger and the levels of food insecurity that prompt warnings can inform ways to help.

World hunger remains one of the most pressing and pervasive problems today. In a world that produces more than enough to feed 8.2+ billion inhabitants, an estimated 733 million people still face hunger. Food insecurity is caused by factors such as poverty, conflict, extreme weather, economic instability, and may be exacerbated by long-term issues such as climate change.

Amid the many headlines and reports about food crises, understanding hunger and the levels of food insecurity that prompt warnings can inform ways to help.

Understanding levels of hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition

At its basic level, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) says hunger is an uncomfortable or painful physical sensation due to insufficient consumption of dietary energy. It becomes chronic when a person doesn’t regularly consume sufficient calories.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), malnutrition refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. This can result in conditions such as obesity, micronutrient-related malnutrition (inadequate vitamins or minerals), and undernutrition, which includes wasting (low weight for height), stunting (low height for age), and being underweight (low weight for age). These factors weaken the body, making it more susceptible to disease, contributing to cognitive and physical impairments, and potentially leading to death.

Classifying food insecurity levels

It’s important to know that acute food insecurity is considered short-term. It’s characterized by a person's inability to consume adequate food that puts their lives or livelihoods in immediate danger. Chronic food insecurity is a long-term problem that usually stems from poverty and other persistent factors.

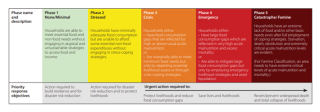

To determine the phases of acute food insecurity, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) uses tools and methodology to classify the severity and magnitude of food insecurity in countries and regions. It divides acute food insecurity into five phases to inform decision making and interventions.

These five levels are: Phase I-Minimal, Phase II - Stressed, Phase III - Crisis, Phase IV - Emergency and Phase V - Catastrophic-Famine. Each phase has a set of criteria that can also be viewed fully on the IPC website. Famine is the highest level of acute food insecurity classification—catastrophic—and has a specific definition with precise indicators that must be met to be classified as famine.

Many levels of hunger where Mary’s Meals operates

In many of the 16 countries where Mary’s Meals operates, acute food insecurity may be interconnected with one or several factors like economic instability, extreme weather events or conflict and displacement.

For example, in Tigray, Ethiopia, after suffering through COVID, followed by a two-year civil war, it endured a drought that adversely affected food production and water supplies further impacting regional food insecurity. The outlook for five million people in Tigray is to remain in Phase III Crisis levels of acute food insecurity through May. This makes the Mary’s Meals school feeding for 110,000 children lifesaving.

In Haiti, ongoing gang violence and turmoil have displaced a half million people, and almost 50% of the (11+ million) population faces crisis and emergency levels of acute food insecurity. Here, Mary’s Meals supports school feeding for 175,000 children for whom a school meal is likely to be their only food that day. School meals provide urgent nutrition, access to education and help to keep children engaged in school, not gangs.

School feeding is a key intervention to prevent child hunger

School feeding is a key intervention to prevent child hunger while providing access to education. It also acts as a social safety net for children and their families. The daily provision of meals draw children to school where they can gain an education that can help break the cycle of poverty and hunger. With consistent meals, children receive the nutrients needed for health, growth and learning.

Globally, school meals are now recognized as a key intervention to improve education access and ensure inclusive and effective learning environments. In 2023, school meals were added as an official indicator to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4: Quality Education. This is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals that comprise the 2030 Agenda, which is a global plan of action for people, prosperity and the planet.

By knowing the levels of acute food insecurity and hunger, people can parse headlines to understand the urgency behind the warnings and decide how best they can help.

“I hope we never lose a sense of outrage that any person or child in this world of plenty would face death by starvation. But what we do with these feelings—and the action they prompt—is ultimately what matters most, and our actions do make a difference,” said Mary’s Meals founder and CEO Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow.

Image courtesy of FAO